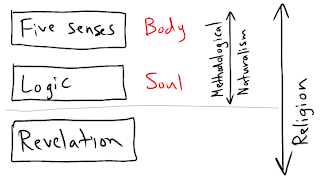

He insists that ID is not just a negative case of pointing how evolution is an insufficient explanation, but that ID is a positive scientific statement, "based on what we know, not on what we don't know". He says,

there is a cause of which we know that is capable of building the kind of information that we see arising in the history of life, in the Cambrian period, for example. And that cause is intelligence.Dr. Meyer likes to say that he bases his conclusions on a standard method of scientific reasoning, called "inference to the best explanation".

Darwin had a principle of reasoning that he also used which was called the vera causa principle. The idea is that when you're trying to explain an event in the remote past you should look for causes that are now in operation, causes that are known to produce the effect in question. Well, as I was studying that in graduate school I asked myself the question, What is the cause now in operation that produces digital code, that produces circuitry? And the answer from our uniform and repeated experience is intelligence.From that, he concludes that an intelligent being created life and the universe.

Here's the problem. According to his logic, we should conclude that humans created life and the universe, since our uniform and repeated experience tells us that humans create digital code and circuitry. We certainly have no uniform and repeated experience of gods creating digital code. Nor do we have any uniform and repeated experience of unembodied intelligent agents designing circuits. Just humans.

So, by Dr. Meyer's logic, we should conclude that humans created life and the universe. Done.

You'll be relieved to hear that this logic is faulty. No, you are not responsible for creating yourself and all your friends.

Dr. Meyer implies that the best explanation of the order we see in the universe is intelligence. But why is that the best explanation? Who says? I admit that it's satisfying in an intuitive sense... we deal with intelligent agents all the time (other people), so what's the problem with adding just one more?

However, the universe is not there to satisfy our intuitions. It can contradict our intuitions quite happily, thank you very much. So, intuitions aside, how might we gauge a good vs. bad explanation? Probability. The most probable explanation could be considered the best explanation.

Question: What is the probability that an unembodied, timeless intelligent agent created the universe and designed the life therein?

Answer: Hard to say, since we really have no basis for comparison.

Question: What is the probability that humans mistakenly believe the universe was created by an intelligent agent?

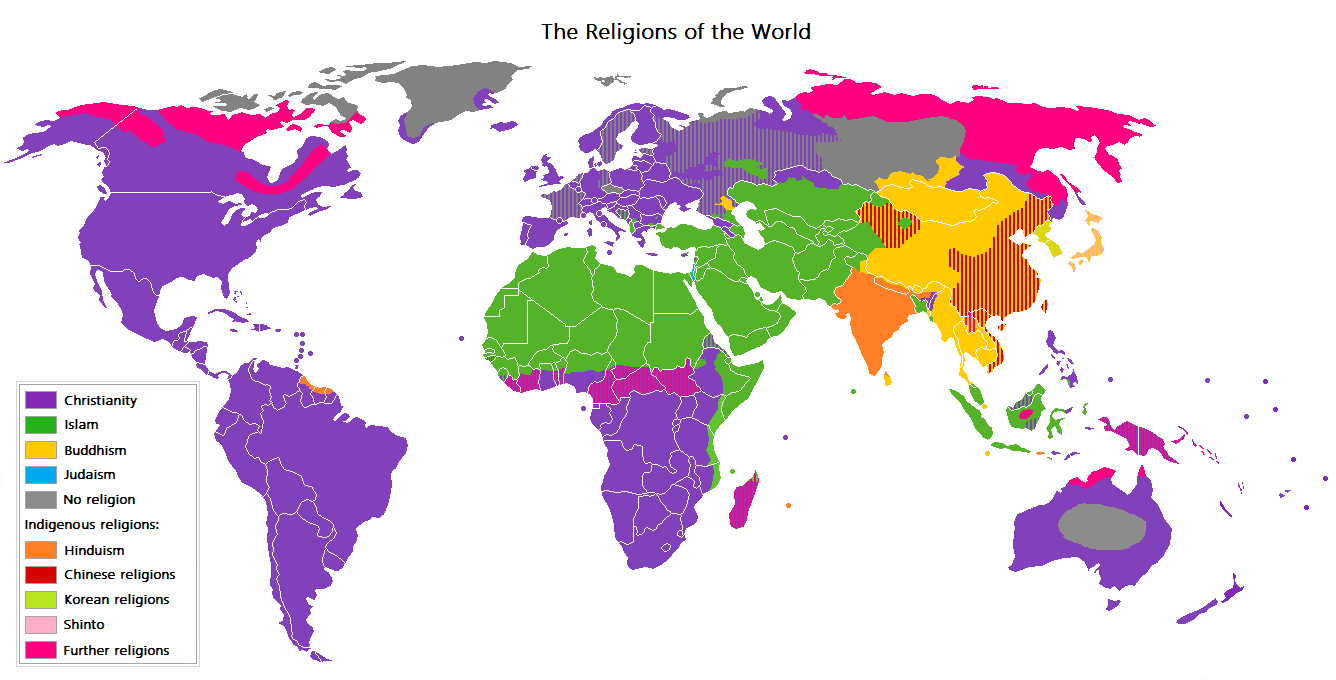

Answer: Well, on this topic we have lots of data. Human psychology is full of examples of delusion, many of them clearly anthropomorphic in nature. Humans used to believe that thunder and lightning were the gods getting angry. Those who believe they've seen aliens usually draw them as humanoid. Look at all the different religions, each with its own human-like god (or gods). It's clear that humans are susceptible to anthropomorphic delusions.

Darwin showed us that information and design can emerge by natural causes.

So, what is your inference to the best explanation? A magic, invisible, unembodied, intelligent creator? Or the operation of natural causes, viewed through a distorted human lens?